AUKUS alliance and France in Indo-Pacific : towards non alignment ?

AUKUS and the Eurasian Encirclement Manoeuvre

The new alliance between the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom (AUKUS) in the Indo-Pacific heralds a new escalation in the geopolitical rivalry between the US and its Anglo-Saxon allies against China.

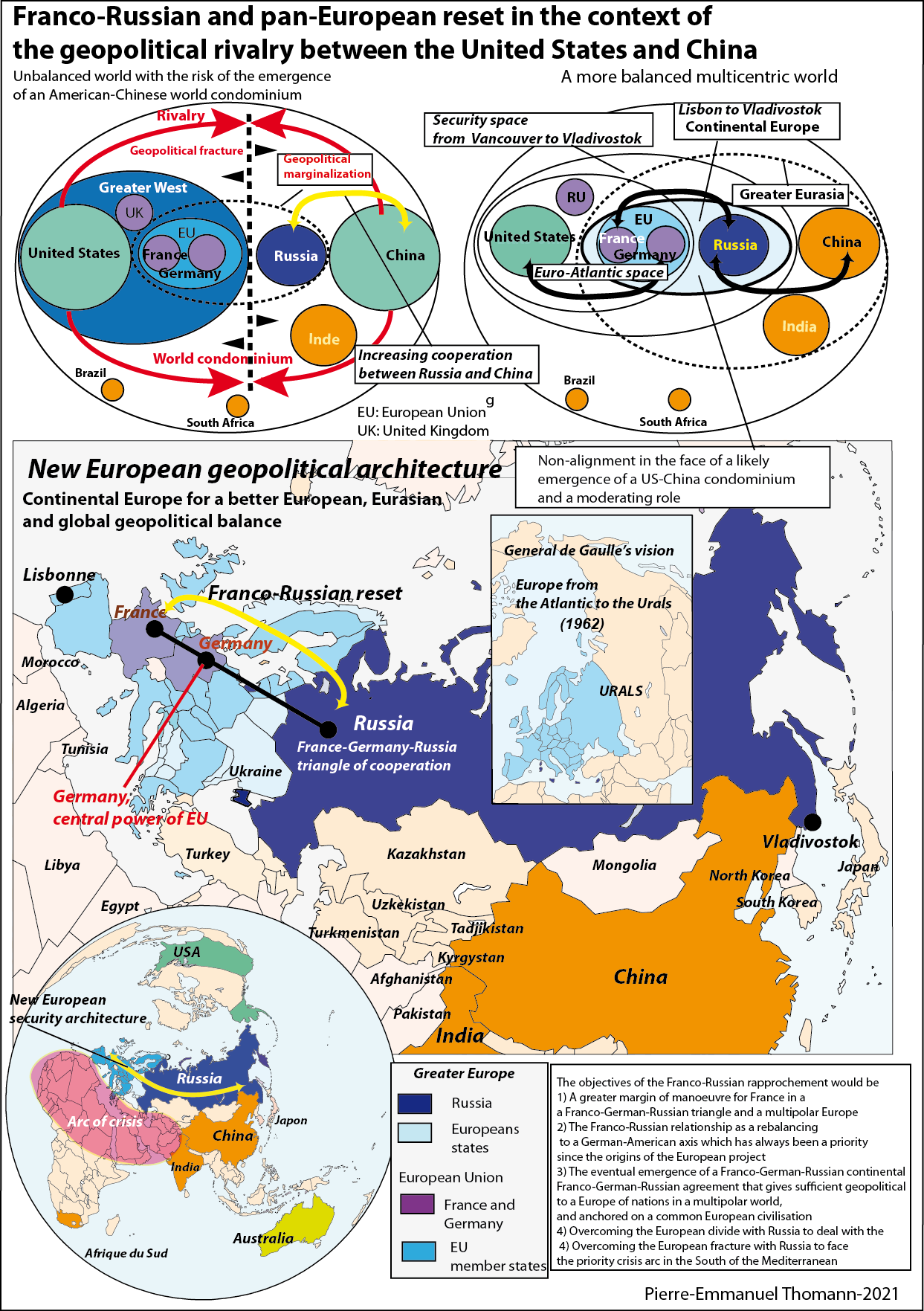

In order to interpret the emerging geopolitical configuration that resulted from the creation of the AUKUS alliance , the stakes must be approached on a global scale and not only in the Indo-Pacific zone in order to underline its deep roots.! (Map 1: US geopolitical strategy against Russia and China in the context of power rivalry).

It should be remembered that for the United States, the Indo-Pacific doctrine3 is only the Asian part of a wider manoeuvre that consists of encircling Eurasia, the other part being the East European front against Russia. AUKUS is therefore part of the Anglo-Saxons’ desire to position themselves at the top of the hierarchy of powers. This alliance of the three Anglo-Saxon countries in the Indo-Pacific is exclusive, as it stems from the Anglo-Saxons’ objective of slowing down the emergence of the multi-polar world on a global scale, notably against China but also against Russia. Even if the Indo-Pacific area becomes a priority for the United States, the European theatre remains relevant.

This alliance of the three Anglo-Saxon countries in the Indo-Pacific is exclusive, as it stems from the Anglo-Saxons’ objective of slowing down the emergence of the multi-polar world on a global scale, notably against China but also against Russia. Even if the Indo-Pacific area becomes a priority for the United States, the European theatre remains relevant. The global strategy of the Anglo-Saxons also consists in preventing the possible emergence of a Western European bloc around France and Germany, with an eventual agreement with Russia, or even China by continental route. The United States cannot enlist Russia against China, because not only does Russia have no interest in a geopolitical rift in Eurasia with China, but if Russia is no longer an adversary, there would be no obstacle to a pan-European agreement, resulting in the obsolescence of the Atlantic alliance and the United States’ leadership role in Europe. The United States also does not want to leave the European theatre, because in the event of a conflict with China, it believes it is necessary to prevent Russia from taking advantage of a strategic vacuum in Europe, in order to avoid a war on two fronts.

The AUKUS is thus just another escalation in the US grand strategy towards Eurasia, with the aim of preventing a rival power from controlling the coastal areas of that continent (and endangering its supremacy). It has its roots in Spykman’s geopolitical doctrine (containment of the USSR in the 1950s), which has been extended to the present day. The designation of China and Russia as adversaries of the United States under President Donald Trump, a priority pursued by Joe Biden, stems from this.

The sidelining of France is obviously not accidental, as France has been at the forefront of promoting European strategic autonomy, but also a new European security architecture with Russia. This is a warning to Germany, which wants to preserve its trade links with China and its energy supplies with Russia.

The presence of the United Kingdom under the banner of the « Global Britain » doctrine in this Indo-Pacific alliance demonstrates that its deep geopolitical vocation is global. The United Kingdom is the only European state, along with France, that also has territories in the Indo[1]Pacific area, although they are smaller than France’s

In Europe, the objective of the Anglo-Saxons, mainly the United States and the United Kingdom but also their Atlanticist allies in Central and Eastern Europe, is to avoid an understanding between Russia, Germany and France, in particular by encouraging a crystallisation of the rift between Ukraine and Russia. From One Triumvirate to Another French diplomacy, by integrating the American Indo-Pacific doctrine in 2018, aligned itself with the priorities of the Anglo-Saxons without the appropriate restraint to defend its strategic independence. As a result, it has not obtained any prior guarantee of its participation in decisions, and is now being pushed out of the heart of the alliance by the triumvirate of the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom. Yet France participated in April 20215 in naval manoeuvres in the Bay of Bengal (Indian Ocean) with the Quad6 countries: the United States, Japan, India and Australia, and in the Pacific with the United States, Australia and Japan, in May 2021, provoking criticism from China denouncing the emergence of an « IndoPacific NATO » according to a Cold War logic.

From One Triumvirate to Another

This crisis reminds us of another triumvirate, the one that General de Gaulle had proposed to the United States and the United Kingdom in 1958 and which he had not obtained. Alliances between Anglo-Saxon nations are always exclusive, a lesson of history and geopolitics that French diplomacy has still not learned. The « Five Eyes », the close alliance of the intelligence services of Australia, Canada, the United States, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, has existed since 1941 and continues to this day

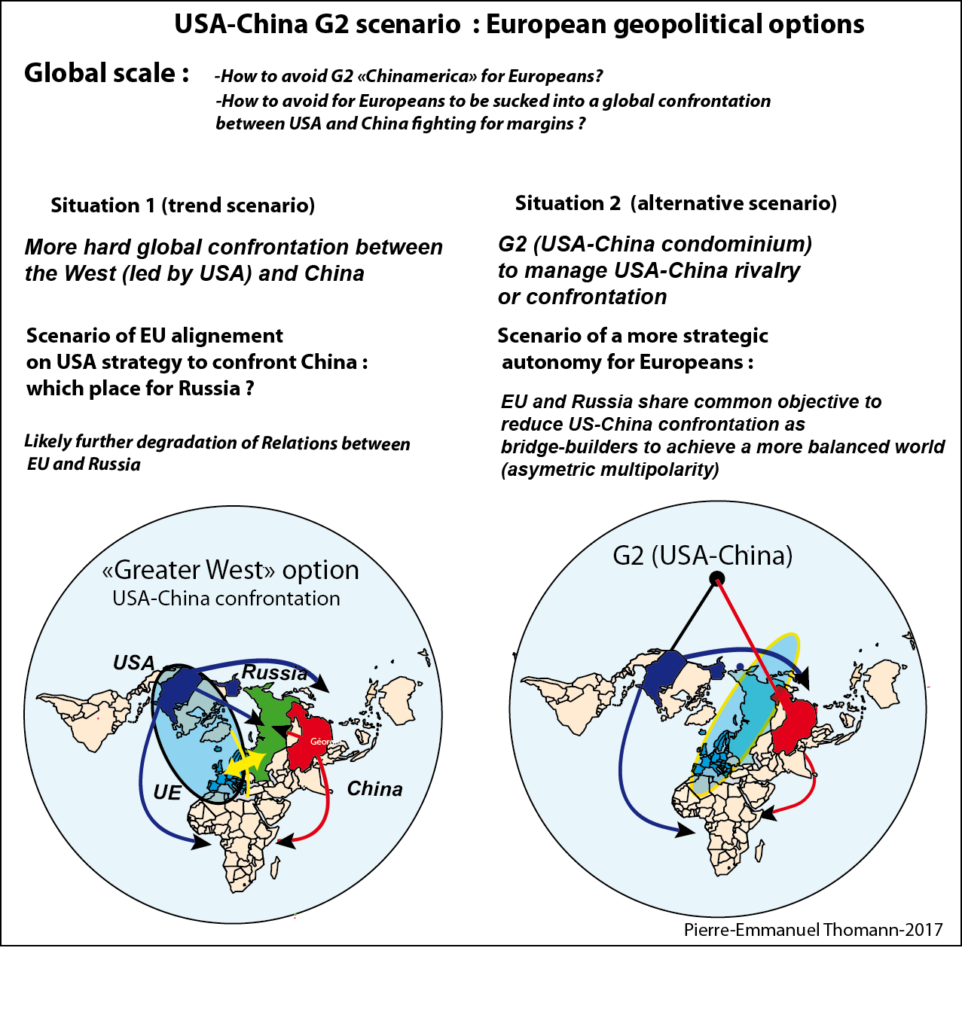

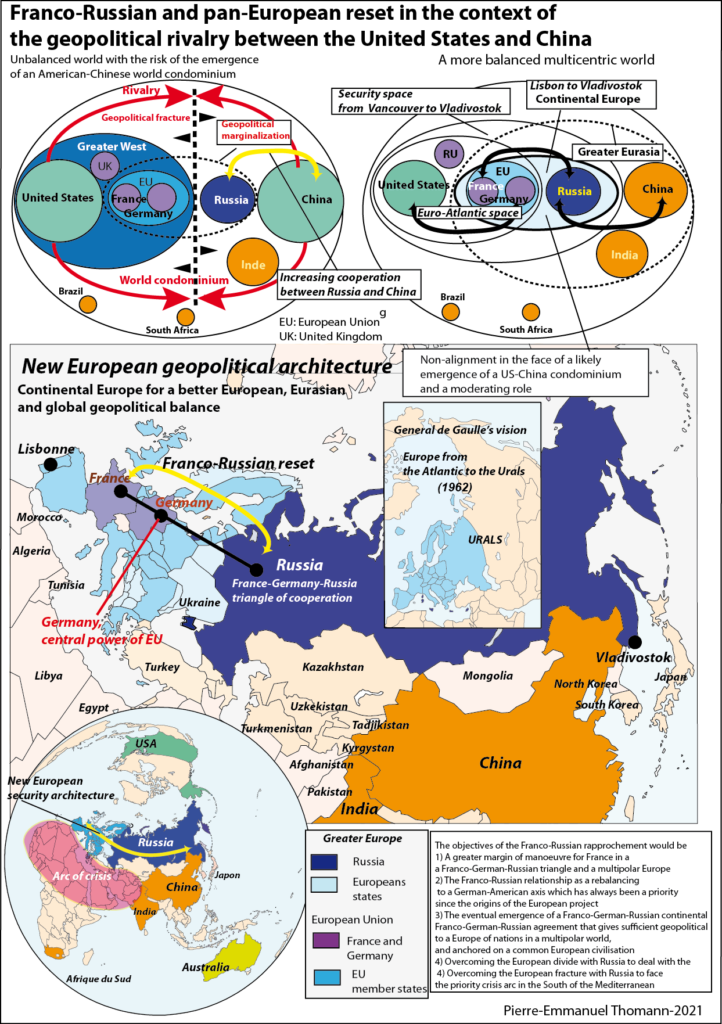

This episode led General de Gaulle, after his failure to obtain equal status with the United Kingdom in NATO, to commit himself to the Franco-German alliance with the Elysée Treaty (1963), and later to anticipate the emergence of a « Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals » with Russia. Since the Anglo-Saxon triumvirate in the Indo-Pacific has pushed France aside, this is an opportunity for France to rebalance its alliances, as General de Gaulle had tried to do.

France’s Loss of Strategic Independence

The Anglo-Saxons expect France to fall definitively into line with a subordinate role

The lesson of this crisis is however the following: integrating the Anglo-Saxon Indo-Pacific strategy, but trying to preserve a tactical margin of manoeuvre, is obviously not enough. The mistake of French diplomacy (since the departure of General de Gaulle?) was to persist in believing that a privileged position could be granted to France by fitting in with Anglo-Saxon geopolitical priorities (by subscribing to the Indo-Pacific doctrine / and by approving NATO enlargements), while preserving a tactical margin of manoeuvre (by obtaining arms contracts for example). Predictably, Donald Trump’s « America First » doctrine continues with Joe Biden.

The more France moulds itself along the lines of the Anglo-Saxons’ geopolitical priorities since the end of the Cold War, as in ex-Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine and today in the Indo-Pacific, the less it will be respected. France’s search for tactical autonomy in these different manoeuvres inevitably leads to increasing intransigence on the part of the United States with regard to the degree of France’s allegiance. Hubert Védrine’s formula, « friends, allies, but not aligned », seems less and less defensible in the systemic rivalry of the confrontation between the United States and China on the basis of « either you are with us or you are against us ».

The more France moulds itself along the lines of the Anglo-Saxons’ geopolitical priorities since the end of the Cold War, as in ex-Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine and today in the Indo-Pacific, the less it will be respected. France’s search for tactical autonomy in these different manoeuvres inevitably leads to increasing intransigence on the part of the United States with regard to the degree of France’s allegiance. Hubert Védrine’s formula, « friends, allies, but not aligned », seems less and less defensible in the systemic rivalry of the confrontation between the United States and China on the basis of « either you are with us or you are against us ».

France deplores its eviction from an alliance that precisely reinforces the logic of blocs, the Anglo-Saxon bloc, against China. Moreover, France’s Indo-Pacific strategy aims to establish strategic partnerships with all the states in the zone, except China.

This posture therefore runs counter to a multi-polar approach. However, multilateralism is not applicable without the prior acceptance by the powers that count of a multi-polar order, including China, because there is no international normative order without a spatial and geopolitical order. France also supports the strategic autonomy of its Southeast Asian partners. Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian spoke of a « multi-polar Asia » to avoid Chinese hegemony, but at the cost of aligning itself too closely with Anglo-Saxon priorities by reinforcing its own supremacy.

French diplomacy today no longer promotes a multi-polar world (and even less so a multipolar Europe) and de facto no longer challenges the unipolar vision of the Anglo-Saxon countries on a global scale and in Europe, contrary to the Gaullist vision

Geopolitical Response from France

A new geopolitical manoeuvre should respond to the Anglo-Saxon manoeuvre to push France and Europe aside, in addition to countering China and Russia. Today, the emerging geopolitical configuration lends itself once again to a rebalancing of alliances, within the framework of this new Great Game that is unfolding on the margins of the Eurasian continent, in Europe and in the archipelagos of the Indo-Pacific space. A geopolitical strategy is the anticipation of the space-time of others (allies and enemies).

It is now up to France to retaliate by acting on the geopolitical configuration and not only by tactical adjustments. In order to avoid being sucked without limits into the growing confrontation between China and the Anglo-Saxon countries, led by the United States, France could promote an alternative posture of non-alignment, while asserting its own red lines with respect to China. France’s vocation as a balancing power is to promote a better geopolitical balance in the world between powers and not to lock itself into an « alliance of democracies » under Anglo-Saxon leadership. It risks losing its independence and moving away from its priority national interests in Europe and the Mediterranean. Moreover, if the AUKUS fails to mobilise beyond the Anglo-Saxon circle in the face of the reluctance of Asian or European states to mobilise, notably for reasons of economic interests and interdependence with China, but also to avoid an escalation, a third way will subsequently be considered a judicious choice.

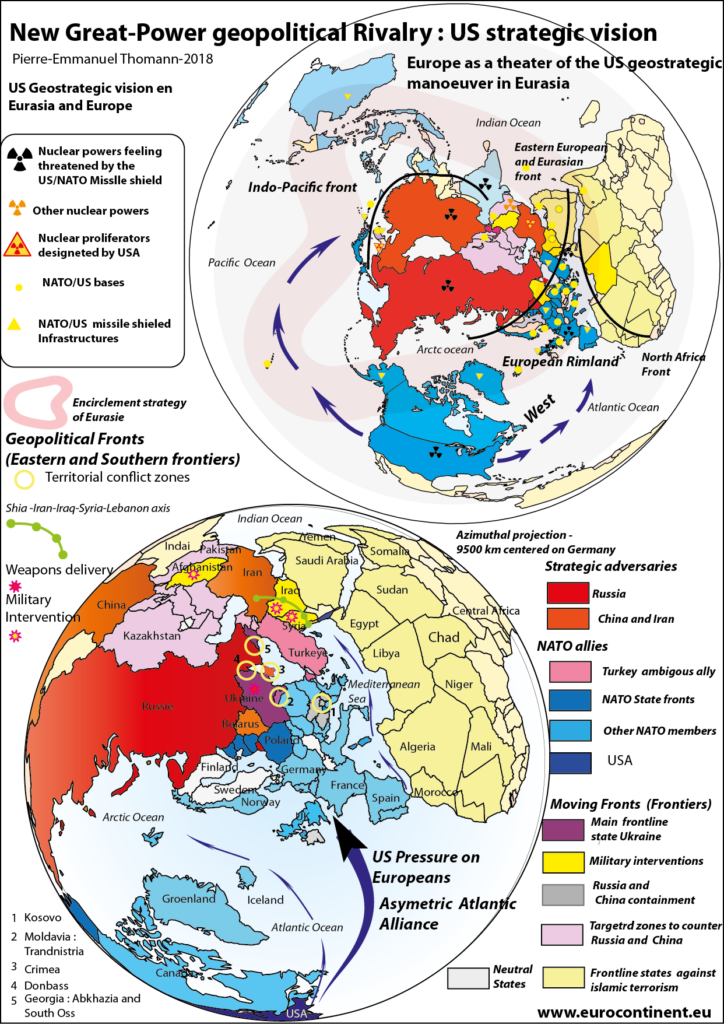

The risk of the emergence of an American-Chinese condominium, where the leaders of the two rival states negotiate agreements at the expense of the other states on the brink of confrontation, similar to the Cold War between the US and the USSR, must also be avoided. (Map 2: Geopolitical options of Europeans in the face of US-China rivalry).

France’s new posture should stem from an identification of its own priorities at the global, European and national levels.

France has a territorial presence in the Indian Ocean (Mayotte, Reunion, French Southern and Antarctic Territories) and the Pacific (New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna, French Polynesia and Clipperton) with a population of approximately 1.6 million and a sovereignty military force of more than 7,000 men. France has the second largest maritime area in the world and more than 90% of its exclusive economic zones (EEZ) are located in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

France must defend itself against any potential threat to its territory in the Indo[1]Pacific area, which must not fall under either Chinese or Anglo-Saxon hegemony. It is dangerous to join in an escalation that could turn its territory in the Indo-Pacific area into an issue between the United States and China and a target. The deterioration of security in the collision zones between the two powers (including the Indo-Pacific) is real.

However, for France to be credible in terms of the defence of its territory, but also vis-à-vis its allies, a reinforcement of its naval aviation capabilities should be a priority to ensure a more autonomous defence of this territory which is the size of Australia.

An unfailing will to maintain its presence in New Caledonia (which holds 25% of the world’s nickel resources) threatened by independence movements supported from outside (today China, yesterday Australia and New Zealand

should be reaffirmed. Diversification of its alliances and a more sensitive rapprochement with countries that do not wish to fall under China’s domination, but also wish to preserve their margin of manoeuvre, such as India, Indonesia, New Zealand, South Korea, Japan and Vietnam, would also be desirable. The stakes of the Indo-Pacific region should not divert France from its priority geopolitical interests by playing the role of a proxy for the Indo-Pacific doctrine in the wake of exclusive Anglo-Saxon interests. The priority adversaries of the Anglo-Saxon triumvirate, China and Russia, are not the priority adversaries of France. Neither China nor Russia threatens France today. France’s main enemy remains Jihadism, which is unfolding in the arc of crisis south of the Mediterranean to the Middle East and spilling over into its territory. Cooperation between France and the United Kingdom to maintain their nuclear power status, but also with the United States and the Anglo-Saxon countries, in the fight against Jihadism must obviously continue according to the principle of variable coalitions. In the event that the territory of France or its allies in the Pacific and Indian oceans were directly threatened by China, France should be able to cope by increasing its own military presence and negotiating alliances according to the new configuration. However, a premature bloc logic is likely to provoke a self-fulfilling prophecy leading to escalation against China. France would also have an interest in reducing the risk of nuclear escalation in the Indo[1]Pacific region, now reinforced by the nuclear proliferation induced by the delivery of US nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, an example that could be followed by China and Russia vis-à-vis their allies.

France and Europe should not consider themselves exclusively as « maritime democracies », like the three founders of the AUKUS alliance23, but also as continental powers and should make the most of their Eurasian depth to fit into the emerging multi-polar world. From the point of view of a policy of diversifying and securing energy and commercial flows, the opening of a Eurasian corridor and an Arctic corridor would offer an alternative to the maritime route on the Suez Canal – Red Sea – Indian Ocean – Strait of Malacca – Pacific Ocean axis. The connection to the new Chinese Silk Roads could be advantageous if the Europeans coordinated to negotiate the modalities with China so that these flows could be beneficial to all countries by ensuring that trade could be rebalanced. Russia, but also Germany, Italy and central European countries such as Hungary are already connected to the new Silk Roads, while it is more recent for France.

What is missing is a coordination between European countries to have more weight vis-à-vis China. Trade and transit routes with Russia and Central Asia could be strengthened in parallel. Links with the Siberian area (Europe’s energy hinterland), Central Asia and the Far East would be secured with these new corridors: the network would be made up of a bundle of continental and maritime lines crossing the Eurasian continent and maritime axes in the South (Cape Route and Suez) and in the North (North-West Route and Northern Route in the Arctic Ocean). A policy of geographic tightening, that favours production and trade flows on short circuits, with a plan for industrial relocation on French soil and its European neighbours, would also be adequate to reduce dependence on anarchic and distant flows. The headlong rush towards globalization based on the ideology of total free trade, with Asia-Pacific as the sole centre, could thus be avoided. Geopolitical Consequences for France: Non-Alignment and Pivot towards Russia For France, the Greater Europe in its continental depth, notably on an axis running from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the Mediterranean/Sahel – Indian Ocean – Pacific Ocean axis, constitute two priority axes, in addition to the Euro-Atlantic axis. It would therefore be preferable to move away from an Indo-Pacific doctrine that is based on any logic other than that of France’s priorities and to adopt its own positioning with broader alliances. France, as a balancing power, should seek to avoid the hegemony of both China and the Anglo-Saxons and promote a policy of non-alignment with Germany, Italy, Hungary and Russia in Europe, and India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and New Zealand in Asia, as well as all the states that do not want to be sucked into this confrontation, in order to avoid an American-Chinese condominium. The principle of variable coalitions should be preferred to the illusory unity of the European Union or NATO on this issue.

The question of the inadequacy of the priorities of NATO and the EU, organizations created in the context of the Cold War, in the new European and global geopolitical configuration is clearly raised for France.

The strengthening of cooperation programmes in the field of defence is necessary, above all at the bilateral level and within restricted coalitions to promote more strategic independence for France and its European partners, in parallel with a rapprochement on the perceptions of security and the geopolitical aims of the European project, which are currently too divergent. Russia could adopt a non-alignment posture in the event of a strengthening of the US-China confrontation and avoid a drift towards a logic of antagonistic blocs. Russia will not align itself in an alliance against China. In Europe and in the world, it is therefore also with a pivot from France to Russia that France could widen its margin of manoeuvre. A Franco[1]Russian rapprochement would re-establish a relative balance with the Anglo-Saxons, and reduce the risk of a too close tactical agreement between Russia and China, with the more distant goal of promoting a new European security architecture. France’s recurrent attempts at Franco-Russian rapprochement, with General de Gaulle (Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals, 1963), President Mitterrand (The European Confederation, 1991), President Jacques Chirac (Paris-Berlin-Moscow Axis against the Iraq War, 2003), Nicolas Sarkozy (New European Security Treaty after the Russia-Georgia war, 2008) and Emmanuel Macron (New European Security Architecture, 2018), have not been followed by any lasting effect. This in no way detracts from the interest of this vision, and for good reason, as it is the only approach that would allow us to act on the geopolitical configuration in a systemic manner, and not to be satisfied with tactical adjustments that have no effect in the long term, hence the obstacles from states that do not wish to see France preserve its rank as a power. It goes without saying that France could propose in return a more constructive synergy with Russia with regard to European stability, but also security issues with regard to Jihadism in the Mediterranean, the Near East, the Middle East and Africa, and restraint with regard to the respective zones of influence. (Map 3: Franco-Russian rapprochement and continental axis from the Atlantic to the Pacific in the context of geopolitical rivalry between the United States and China).

By overcoming the current rift with Russia, France could concentrate on its priority axes with the states that favour this approach: the outline of a Europe from the Atlantic to the Pacific, such as General de Gaulle had anticipated, to rebalance Europe and the world with regard to Anglo-Saxon and Chinese hegemonic pretensions and to ensure its security on the crisis arc south of the Mediterranean and its own territory.